SEVENTY-FIVE YEARS AFTER HE BROKE BASEBALL’S COLOR BARRIER, A MAJOR AUCTION OF NO. 42’S MOMENTS AND MEMORIES

By Robert Wilonsky

The tale of Jackie Robinson’s first meeting with Brooklyn Dodgers President Branch Rickey, on Aug. 28, 1945, has been recounted and reshaped so many times it long ago slipped from memory to mythology. Each retelling, in print and on film, is a little different; each detail slightly tweaked. Yet there is no changing the outcome: Robinson’s ascension from Negro Leaguer to the first Black ballplayer in the minors and majors.

► EVENT

WINTER PLATINUM NIGHT® SPORTS AUCTION 50052

Feb. 26-27, 2022

Online: Ha.com/robinsondodgers

INQUIRIES

Dan Imler

310.492.8692

DanI@HA.com

There is little dispute, too, that Robinson asked Rickey if he wanted a man who was afraid to fight back against fans, opponents, umpires, newspapermen and even teammates who would deny him and degrade him. There is no arguing, either, that Rickey told his recruit he wanted a man with guts enough not to.

“It is testament to Rickey’s sophistication and foresight that he chose a ballplayer who would become a symbol of strength rather than assimilation,” Jonathan Eig wrote in 2008’s bestseller Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season. “It is testament to Robinson’s intelligence and ambition that he recognized the importance of turning the other cheek and yet found a way to do it without appearing the least bit weak.”

So the story goes, told in each man’s autobiographies and interpreted by others forever after: Branch Rickey asked Jack Roosevelt Robinson if he could turn the other cheek, for as long as it took. “Mr. Rickey,” Robinson said, “I’ve got to do it.”

Here, in black and white, is how certain Robinson was: At the end of March 1946, one month before his debut as one of the Dodgers’ minor-league Montreal Royals, Robinson filled out a standard questionnaire provided by the American Baseball Bureau. Robinson was asked about his “ambition in baseball.” In the space provided, he wrote: “To open door for Negroes in Organized Ball.”

That questionnaire, which also notes Robinson’s year with the Kansas City Monarchs and credits Rickey as the person to whom he owes “the most” in his baseball career, has been oft-cited in Robinson lore. It appears in Eig’s book and others, and was mentioned repeatedly as a highlight of the legendary Barry Halper Collection auction in 1999 – the first and last time the document was publicly available.

Almost a quarter century later, Robinson’s 1946 questionnaire returns as one of the centerpieces in Heritage Auctions’ Feb. 26-27 Winter Platinum Night® Sports Auction. The framed document, which bears a sticker from its 1999 Sotheby’s sale, has been authenticated in recent years by Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA) and Beckett Authentication Services.

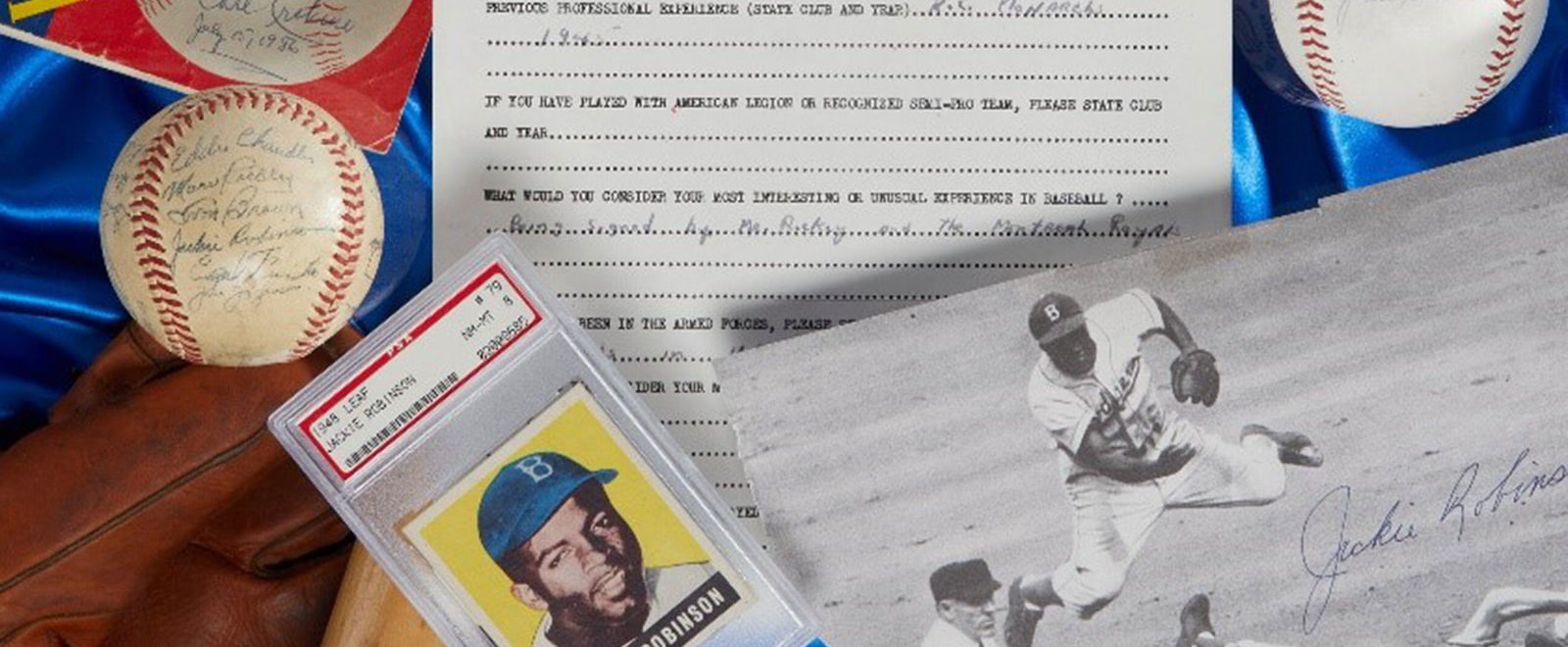

The document is one piece of an extraordinary assemblage of nearly 50 historic Robinson and Brooklyn Dodgers-related items being offered in the February event. They all come from a single collector, a New York native, who spent years amassing these historic moments, beginning at the Halper sale.

“Jackie Robinson has always been a foundational figure in our field, but I think the appreciation for him and his associated memorabilia has grown exponentially over the last five to 10 years,” says Heritage Sports Vice President Dan Imler. “People have really woken up to his historical impact, and the interest in his elite material has accelerated at a greater rate than for any other figure. The timing of these items coming to auction only adds to the excitement, because there’s such a feverish demand for critically important Jackie Robinson items right now.”

And that questionnaire is at the top of that list, as it serves in some ways as “his manifesto,” as Imler calls it.

“It’s the only item where he’s making a declaration in his own hand of his desire to break the color barrier in baseball,” he says. “We’ve seen other questionnaires like this, because from the 1930s through the ’70s it was a standard document with all players entering the major leagues, but most often what you see is very general content. When players are talking about goals and aspirations, it’s usually related to an achievement within the sport: to win a championship, to set a record, something along those lines.

“Jackie’s questionnaire, on the other hand, clearly shows a much bigger objective.”

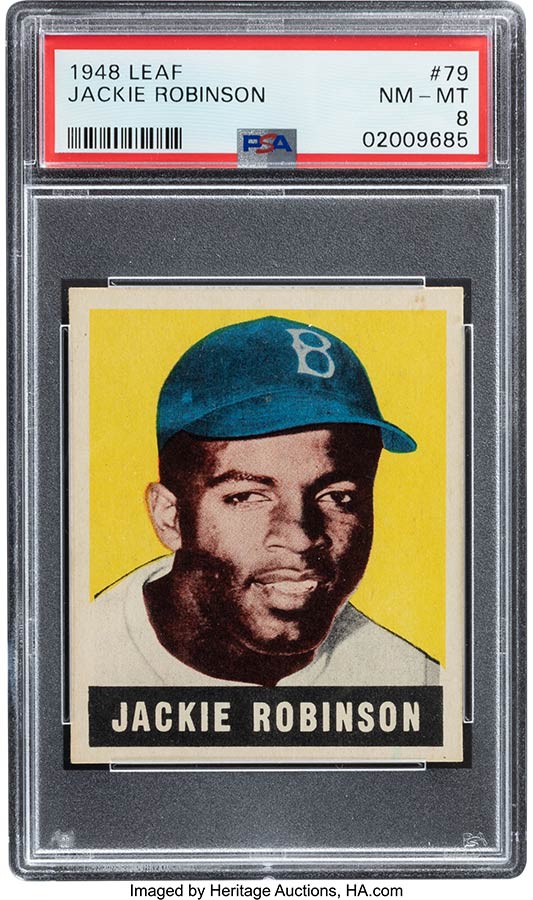

The auction features all one would want from a Robinson and Dodgers event: a signed baseball from Robinson, Gil Hodges’ signed 1951 contract, beautiful-condition cards, including this 1948 Leaf Robinson rookie card graded PSA NM-MT 8. Here, as well, is something of a companion piece to the questionnaire: a 1946 Heilbroner Baseball Bureau Information card filled out and signed by Robinson before his debut as a Royal.

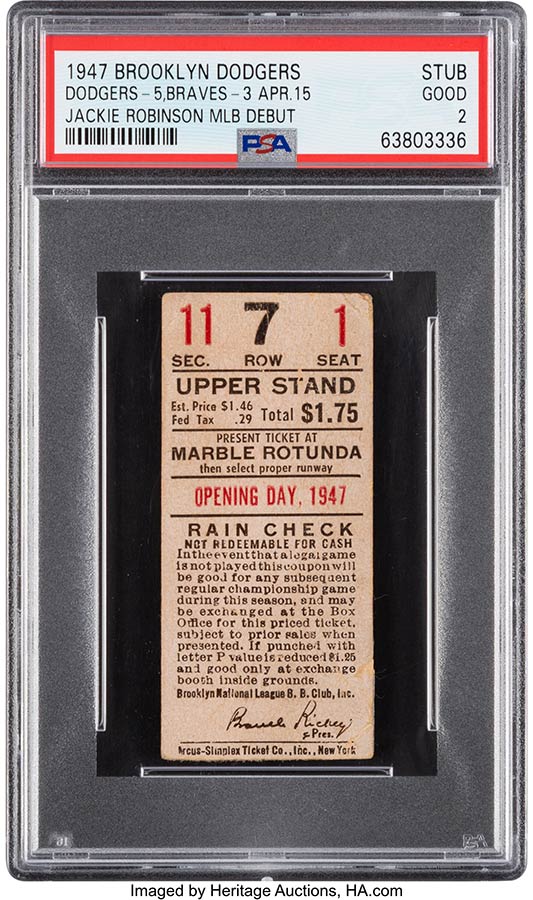

This auction likewise features something seldom seen at auction: a ticket stub from Ebbets Field dated April 15, 1947 – the day Robinson made his big-league debut against the Boston Braves, just five days after signing his Dodgers contract. He went hitless that day in front of 26,623 fans but scored the go-ahead run after reaching base on an error. But no mere box score can hold the weight of that April afternoon in Brooklyn.

“There are defining moments in the life of a nation when a single individual can shape events for generations to come,” President Bill Clinton once said of Robinson’s big-league bow. “For America, the spring of 1947 was such a moment, and Jackie Robinson was the man who made the difference.”

There exist but a handful of these stubs, says PSA, and only two graded “good.” But it almost doesn’t matter the condition of the ticket stub, as this is a significant moment plucked from history that has survived 75 years.

“The bearer of that ticket saw something extraordinary: Jackie Robinson’s professional debut, one of the most important moments in the history of sports – arguably the most important,” Imler says. “That ticket stub, which is so scarce, really puts you in the moment.”

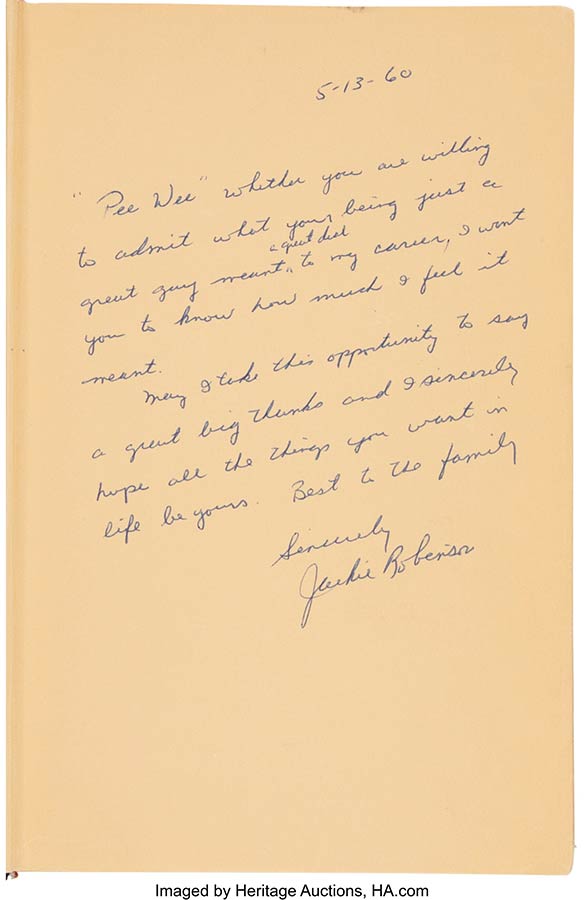

Another centerpiece in this event is an item that bears its own mythology forged by the embellishments of history: a copy of Robinson’s book Wait Till Next Year, in which the author penned a note for his teammate – and friend – Pee Wee Reese.

The film 42 features a scene at Crosley Field in Cincinnati during which Reese, the shortstop from nearby Louisville, Ky., slings his arm around Robinson warming up at first base. All around them spectators hurl racial epithets at Robinson, an all-too-common occurrence during the 1947 season.

“They can say what they want,” Reese tells Robinson before throwing his arm over his shoulder. “We’re here to play baseball.”

It’s a moment recalled by a few observers and memorialized in Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary; Eig, too, wrote in Opening Day about how Reese’s “embrace of Robinson would be described years later as one of baseball’s most glorious and honorable moments.” But there exist no photos of the moment, nor any newspaper accounts of it. Years later, Burns and Eig, among others, would insist it never happened.

Robinson himself said it did occur – in 1948. And though there’s a statue commemorating it in Brooklyn, baseball writer Joe Posnanski deemed it little more than “folk tale” when writing about the embrace for NBC Sports in 2016. But this much we do know, Posnanski wrote: Reese was “a profoundly decent man who rebelled against his own upbringing and embraced Jackie Robinson as a teammate and a friend.”

Which, in the end, is all that really mattered. Maybe Reese didn’t really put his arm about Robinson in Cincinnati, but he stood with him when others only hurled insults at him. The inscription he wrote inside Reese’s copy of Wait Till Next Year lays bare this absolute truth.

“5-13-60, ‘Pee Wee’ whether you are willing to admit what your being just a great guy meant a great deal to my career, I want you to know how much I feel it meant,” Robinson wrote. “May I take this opportunity to say a great big thanks and I sincerely hope all the things you want in life be yours. Best to the family. Sincerely, Jackie Robinson.”

This book comes from Reese’s personal collection, which was auctioned almost two decades ago – and handled by Dan Imler.

“I was in the Reese family home in Louisville packing up a lot of the mementos – the traditional stuff like bats, awards and so on – and we were almost finished when Mark Reese, his son, said, ‘Oh, by the way, I don’t know if you’d be interested or not …,’ and then he produced this book,” Imler says. “When I opened it and read this inscription, I got chills. It’s just unbelievable, this heartfelt acknowledgment to the captain who stood by him. I am just thrilled to see it again.”

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.

ROBERT WILONSKY is a staff writer at Intelligent Collector.