ADD AN ARTFUL TWIST TO THIS YEAR’S TRAVEL WITH DESTINATIONS RANGING FROM AN ACTIVE VOLCANO IN ECUADOR TO A FAMOUS FARMHOUSE IN IOWA

By Andrew Nodell

All great works of art are transportive. While some works simply evoke emotion, others depict an actual location that moved an artist to capture it visually. From the majesty of Ansel Adams’ American West and Frederic Church’s Ecuadorian mountainscapes to the haunting loneliness of Edward Hopper’s deserted New York street corners and Andrew Wyeth’s wind-swept cliffs of coastal New England, these real-life locales (and their artistic representations) can be destinations for art-loving travelers throughout the world. Journey with us as we explore the places that inspired great works and the museums that offer a first-hand view of the art.

Enlarge

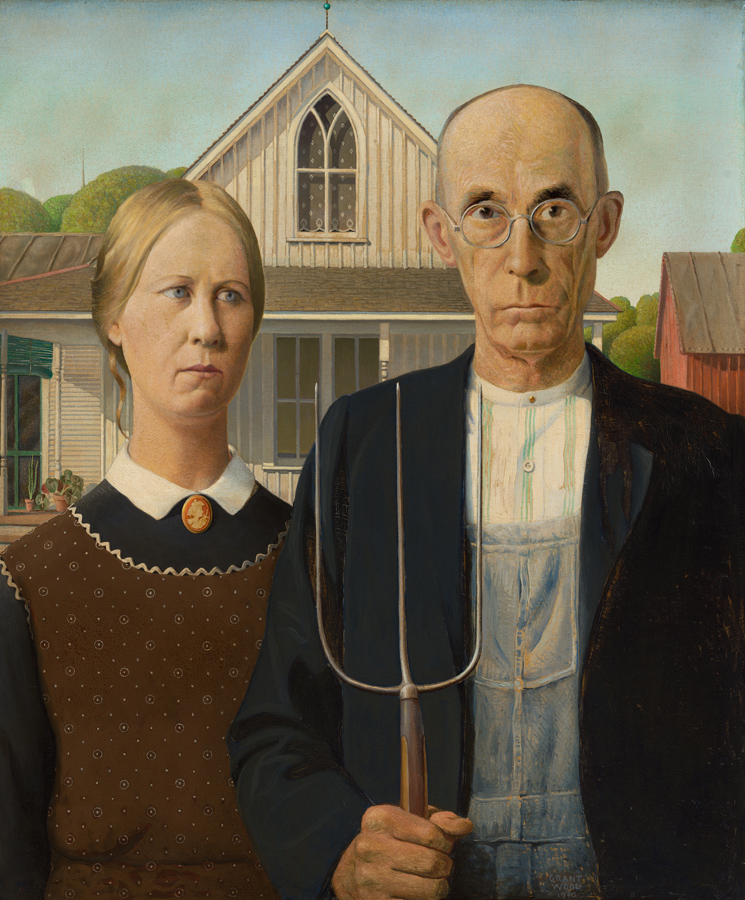

Grant Wood. ‘American Gothic,’ 1930. Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of American Art Collection

Grant Wood, American Gothic, 1930 (Eldon, Iowa)

Art Institute of Chicago

In his most famous work, Iowa native Grant Wood presents a dour duo standing before a modest Midwestern farmhouse. Titled American Gothic, the painting was completed in 1930 and now hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago as one of the 20th century’s most iconic works, both widely celebrated and parodied in American culture. The plain pair in the painting’s foreground was modeled after Wood’s sister Nan and the family’s dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby of Cedar Rapids, Iowa. But the farmhouse with its Gothic-inspired arched window can still be found in Eldon, a close-knit community in the southeast corner of the Hawkeye State with a population of less than 1,000. Wood reportedly discovered the home, also known as the Dibble House, while driving around Eldon with local painter John Sharp in the summer of 1930. According to Wood’s earliest biographer, Darrell Garwood, the artist “thought it a form of borrowed pretentiousness, a structural absurdity, to put a Gothic-style window in such a flimsy frame house.” Wood, who finished his masterpiece at his studio in Cedar Rapids, reportedly never returned to Eldon but requested a photograph of the home to complete his canvas. The circa 1882 home remained a private residence until the late 20th century when it was donated to the State Historical Society of Iowa, where it became a celebration of Grant’s life and work. Modern-day visitors can tour the home’s first floor and stop by the nearby visitor center, which offers rotating exhibitions and even loans aprons and jackets to guests looking to re-create their own American Gothic moment in front of the house.

Public domain

Frederic Edwin Church, Cotopaxi, 1862 (Ecuador)

Detroit Institute of Arts

Best known for romantic landscapes of New York’s Hudson Valley, Frederic Edwin Church found artistic inspiration farther afield in the magnificence of Cotopaxi, an active volcano and the second-highest peak in Ecuador. Church, a member of the Hudson River School, first depicted Cotopaxi in 1853 during the first of two trips to South America and completed at least 10 paintings of this natural wonder during his lifetime. This dramatic work, billed by some art historians as the “apex” of Church’s Cotopaxi series, was completed in 1862 and is now on display at the Detroit Institute of Arts. The Connecticut-born painter’s realistic canvas shows the volcano erupting wildly beside a serene sunrise, smoke billowing past the hazy early morning glow. Some at the time saw this as a parable of the ongoing American Civil War with light being obstructed by darkness and violence. Whether or not Church had this in mind, Cotopaxi is celebrated for realistically and romantically depicting an awesome natural phenomenon that can still be seen today. Visitors can usually hike the area and climb to the summit, but access has been restricted in recent years due to ongoing volcanic activity. From a safe distance, however, travelers can behold a vista similar to that which Church observed more than a century and a half ago.

Gift of Max and Heidi Berry and Ann and Mark Kington/The Kington Foundation

Thomas Moran, The Juniata, Evening, 1864 (Juniata River Valley, Central Pennsylvania)

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

British-born painter Thomas Moran, also of the Hudson River School, was raised in Philadelphia before earning acclaim for his monumental landscapes of the American West including the towering Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, purchased by Congress in 1872 and installed in the Capitol. This earned him the nickname Thomas “Yellowstone” Moran, a moniker he later used to sign paintings as “TYM.” However, before all of this, the talented colorist trained under J.M.W. Turner in his native England and, upon returning to the States, found inspiration in the Pennsylvania countryside – as seen in The Juniata, Evening, now on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In the summer of 1864, Moran traveled to the Juniata River, a major tributary of the Susquehanna in central Pennsylvania, and painted its lush meadows, rising cliffs of sandstone, forested ridges and a lone artist (possibly a self-portrait) dwarfed by the area’s vast natural beauty. Today, visitors can enjoy these views with year-round activities including hiking, fishing, kayaking and camping.

Enlarge

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Bequest of John T. Spaulding/Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

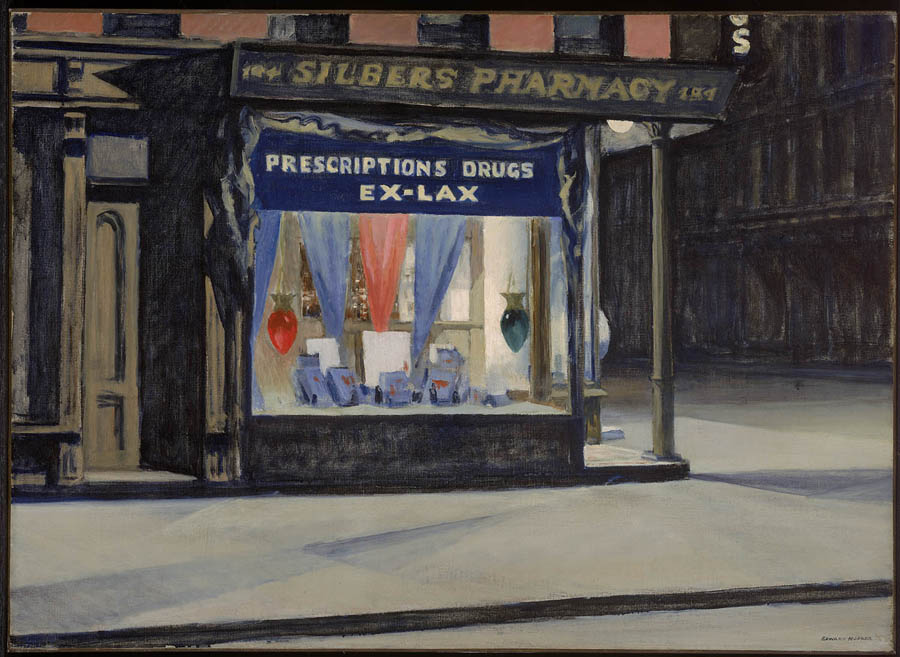

Edward Hopper, Drug Store, 1927 (Greenwich Village, New York)

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Edward Hopper, known for his hauntingly desolate paintings, was famously mum when it came to the exact locations for his urban scenes. However, his 1927 work Drug Store, which shows a warm glow emitting from the windows of its titular subject on an otherwise lonely street corner, bears a striking resemblance to a certain intersection in New York’s Greenwich Village. Now occupied by independent booksellers Three Lives & Company at the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place, the 19th-century storefront with its signature column at the entrance can easily be compared to “Silbers Pharmacy” in Hopper’s work, currently on display at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Additionally, Hopper’s pharmacy bears the number “184,” which aligns with 184 Waverly Place – the address next door to Three Lives & Company. While Hopper never confirmed this in his lifetime, the artist’s longtime studio was located just a stone’s throw away at 3 Washington Square North and, in Hopper’s own words, “The only real influence I’ve ever had was myself.”

Edward Hopper. ‘Corn Hill (Truro, Cape Cod),’ 1930. Oil on canvas. Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Mary and Sylvan Lang Collection

Edward Hopper, Corn Hill (Truro, Cape Cod), 1930 (Cape Cod, Massachusetts)

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio

More easily identifiable are Edward Hopper’s scenes of Cape Cod. It was there that the artist and his wife, Jo, spent summers in the seaside town of Truro, a place known for its sweeping landscapes bathed in golden swaths of light. As the artist once remarked, “All I ever wanted to do was to paint sunlight on the side of a house,” which he expertly executed in Corn Hill (Truro, Cape Cod), completed in 1930 and on display at the McNay in San Antonio. Today, Corn Hill – so named by the Pilgrims for the cache of Native American corn they discovered there upon landing in 1620 – offers a public beach below the hill where several of the turn-of-the-century cottages in Hopper’s work can still be seen. However, a spark from an errant fireworks display in 1937 set the lower row ablaze and they were never rebuilt.

Enlarge

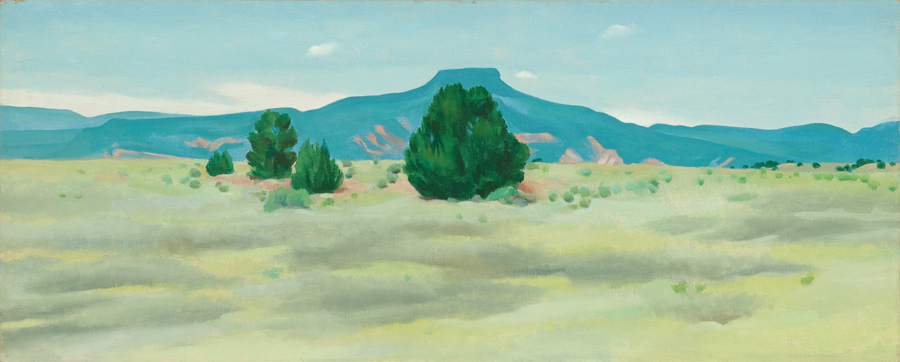

Georgia O’Keeffe. ‘Ghost Ranch Landscape,’ ca. 1936. Oil on canvas, 12 x 30 inches. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Gift of Jerome M. Westheimer, Sr. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. [2005.2.1] Photo: Tim Nighswander/IMAGING4ART

Georgia O’Keeffe, Ghost Ranch Landscape, c. 1936 (Abiquiú, New Mexico)

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Like Edward Hopper, American modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe spent the early years of her career in New York City before discovering inspiration in the natural beauty of rural America. First traveling to New Mexico in 1929, O’Keeffe fully relocated to the town of Abiquiú in 1949, three years after the death of her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. The area’s barren landscape, dotted by short shrubs and trees and punctuated by the imposing volcanic complex of the distant Jemez Mountains, inspired O’Keeffe’s Ghost Ranch Landscape. Today, this work and many others by the artist can be seen at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. The museum also offers seasonal tours of O’Keeffe’s home and studio in Abiquiú.

This gelatin silver print of Ansel Adams’ ‘Half Dome, Merced River, Winter’ realized $8,437 in an October 2023 Heritage auction.

Ansel Adams, Half Dome, Merced River, Winter, 1938 (Yosemite National Park, California)

Rising nearly 5,000 feet above California’s Yosemite Valley, Half Dome is a natural wonder of the American West that has left visitors in awe for generations. Ansel Adams’ photograph of Half Dome and the Merced River, captured in the winter of 1938, has a similar effect. The artist, along with contemporaries Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham, founded Group f/64 on the mission to produce “pure” or “straight” photography that was carefully composed and sharply focused. This goal is expertly achieved with this image, a print of which is held by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Today, thousands of seasoned hikers embark on the 14- to 16-mile round-trip hike to Half Dome and are rewarded with the panoramic views of Yosemite Valley and the High Sierra that inspired Adams nearly a century ago. As the artist revealed in his autobiography, “I knew my destiny when I first experienced Yosemite.”

Public domain

Robert S. Duncanson, Minneopa Falls, Minnesota, 1862 (Mankato, Minnesota)

Cincinnati Art Museum

American painter Robert S. Duncanson was born of European and African ancestry. Renowned for his landscapes, he is considered a second-generation Hudson River School artist and, as a free Black man in antebellum America, encouraged the abolitionist community to promote his work in the U.S. and England. As such, Duncanson is considered the first African American artist to be known internationally and ran in the cultural circles of his hometown of Cincinnati, as well as in Detroit, Montreal and London. Art historian Claire Perry told Smithsonian Magazine, “He invented a unique place for himself that no other African-American had attained at that time.” His 1862 work Minneopa Falls, Minnesota captures a series of cascading waterfalls in Minneopa State Park in Mankato, Minnesota – south of Minneapolis. Many Cincinnati artists at the time were forced to postpone their annual sketching trips in the summer of 1862. Because Duncanson was a free Black man living on the border of the Confederacy, he chose to go north to Minnesota where he was inspired to create this masterful work. The work is currently held by the Cincinnati Art Museum, and visitors to Minneopa State Park can embark on hikes that meander through oak savanna and native prairie grasslands.

© 2024 Wyeth Foundation for American Art / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Andrew Wyeth, Christina’s World, 1948 (Cushing, Maine)

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Andrew Wyeth’s masterpiece Christina’s World depicts a young woman lying in a grassy field, her torso tensely raised as she gazes toward a Colonial farmhouse in the distance. This striking canvas, on view at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, is one of the most iconic works in 20th-century American Art. Wyeth, who summered in Cushing, Maine, found inspiration for this work in his neighbor, Anna Christina Olson, who as a young girl developed a degenerative muscle condition that left her unable to walk. Refusing a wheelchair, Christina preferred to crawl – as seen in this work. “The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless,” Wyeth explained. Christina and the Olson House, built in 1806, inspired Wyeth throughout his career, and the artist is buried (along with Christina and her brother Alvaro) in the Olson family cemetery on the grounds of the home. “I just couldn’t stay away from there,” recalled the artist. “I did other pictures while I knew them, but I’d always seem to gravitate back to the house.” The property is now owned by the Farnsworth Art Museum, which offers tours of the home and grounds. While the Olson House is currently closed due to ongoing restoration work, the Farnsworth offers a virtual tour of the interior on its website.

Public domain

Diego Rivera, Ávila Morning (The Amblés Valley), 1908 (Amblés Valley, Spain)

Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City

Diego Rivera began his work at the National Fine Arts School in Mexico City before being awarded a state scholarship in 1907 for continued studies with Spanish artist Eduardo Chicharro. Searching for new subject matter, Rivera journeyed throughout Spain, where the painter found inspiration in the morning light of the Amblés Valley near the city of Ávila in central Spain. In this early work by the Mexican-born master, Rivera blends the Sierra de Ávila with the soft glow of a morning sky. Visitors can access the summit of Cerro de Gorría in about an hour’s walk from the town of Pasarilla del Rebollar.

ANDREW NODELL is a contributor to Intelligent Collector.

ANDREW NODELL is a contributor to Intelligent Collector.