60 YEARS AGO, WILLIAM HANNA AND JOSEPH BARBERA LAUNCHED A STUDIO THAT FOREVER CHANGED THE CARTOON BUSINESS

By Michael Mallory

In 1998, while working on a book about the cartoon studio created by William Hanna and Joseph Barbera, I had the opportunity to ask Joe Barbera what it felt like to have had such an influence on 20th century culture. His response surprised me.

EVENT

ANIMATION ART SIGNATURE® AUCTION 7173

Featuring a Spectacular Hanna-Barbera Collection

Dec. 9-10, 2017

Live: Beverly Hills

Online: HA.com/7173a

INQUIRIES

Jim Lentz

214.409.1991

JimL@HA.com

“Did I?” he asked. “How could I have an influence?” I reminded him that NASA had recently named a rock on Mars “Yogi Bear” after one of his iconic characters. “I never thought of it,” he replied, before characteristically going for the joke: “Would you mind calling my wife and telling her this stuff?”

Both William Hanna (1910-2001) and Joseph Barbera (1911-2006) are gone, but there is no question that their collaboration, and the decades of entertainment that resulted, had an enormous effect on the popular culture of the world at large, even if they didn’t stop working long enough to realize it.

Two of their most popular shows from the early 1960s, The Flintstones and The Jetsons, continue to live on in television commercials. In the case of The Flintstones, generations of children have grown up with the breakfast cereal and chewable vitamins that continue to bear its name and imagery. They have influenced the American lexicon through such catchphrases as “I would have gotten away with it, too, if not for those meddling kids and their dog!” from the original Scooby-Doo Where Are You! Even politics is not immune, with the uncanny resemblance of Vice President Mike Pence to “Race Bannon” from The Adventures of Jonny Quest remaining a hot topic on social media.

The influence of Hanna-Barbera has even spread to the realm of 20th century American art itself. Due to decades of merchandizing and licensing efforts, it is likely that more homes contain reproductions of the artwork of the late Iwao Takamoto, Hanna-Barbera’s principal character designer, than, say, Andrew Wyeth or even Norman Rockwell.

“In cartoon history, people loved Disney and laughed at Looney Tunes, but generation after generation ‘grew up’ with Hanna-Barbera,” says Jim Lentz, Heritage Auctions’ director of animation art. “The influence of Hanna-Barbera is still seen today on Cartoon Network and Boomerang. Their characters stand the test of time and are some of the most widely recognizable and loved globally today.”

FROM AN ANIMATION industry standpoint, the impact of Hanna-Barbera was even greater; lifesaving, in fact. “They figured out how to make television animation work when people were struggling to take the quality of Disney, Warner Bros., or MGM theatrical animation and make it feasible to be done on the small screen,” says animator, cartoon historian, and educator Tom Sito.

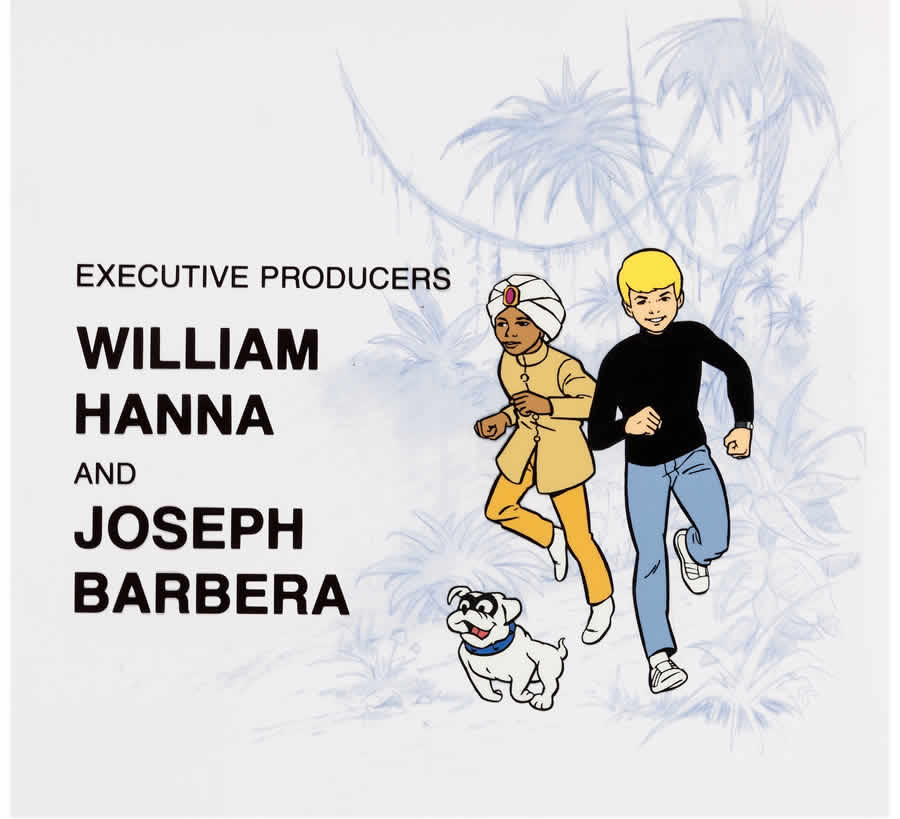

Prior to their foray into television, Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera had been the backbone of the MGM cartoon studio, where they turned out 114 hugely popular Tom and Jerry theatrical cartoons. Barbera handled the story end of things, and Hanna the production and timing, and together they earned seven Academy Awards. Then in 1957, citing the cost benefit of re-releasing old cartoons rather than continuing to make new ones, MGM shut down its cartoon operation, throwing Hanna and Barbera out of work.

Since other theatrical cartoon studios were similarly slowing down, if not shuttering altogether, television presented the only other viable option. So that same year, 60 years ago, the partners founded Hanna-Barbera Productions. The problem was no one had yet succeeded at sustaining a TV cartoon show (Crusader Rabbit, an earlier attempt produced by Jay Ward, was only barely animated). At the time Hanna and Barbera took their gamble, original television animation was for the most part seen only in commercials. Yet, Hanna and Barbera were on a path to dominate American television animation for more than three decades.

The initial challenge for Barbera was developing funny characters that appealed to both young and older audiences. To that end, he relied far more on dialogue and amusing voice work than ever before. For Hanna, the task was to refine the process of “limited animation,” in which a character is drawn on multiple cels, and only the part that absolutely needed to move did move, while the rest of the figure remained stationery.

The initial result was The Ruff and Reddy Show, which debuted in December 1957. Utilizing the talents of fellow laid-off artists from their MGM unit, Hanna and Barbera managed to turn out five-minute cartoons for less than $3,000 each, in rapid succession, rather than the $50,000 they had been spending on each theatrical Tom and Jerry. “That was a big impact for the industry,” says background artist Iraj Paran, who joined Hanna-Barbera in 1967. Hanna and Barbera had proven TV animation was viable, even profitable.

Very quickly, their stable of television characters grew to include Huckleberry Hound, Yogi Bear, and Quick Draw McGraw, and the size of the studio grew to keep up with production. Fortunately, they were able to pick up top talent from other studios that continued to downsize, most notably Disney. “People at the time were worried that the medium itself would disappear,” Sito says, “and Bill and Joe were like a lifeboat for these guys.”

That, though, was still only the beginning. Hanna and Barbera quickly became the kings of TV animation, with Barbera selling more shows in different styles and genres (funny animal, primetime sitcom, action-adventure, superhero), leaving Hanna to figure out how to enlarge the staff to get all the work done. “They provided a lot of jobs,” says layout artist and character designer Jerry Eisenberg, who had briefly worked with Hanna and Barbera at MGM before joining the television studio in 1961. “At one point, there must have five- or six-hundred people.”

Much of the staff was comprised of veteran animators, even pioneers of the art form. “One day I was roaming around the studio and I see Dave Tendlar,” recalls layout artist Willie Ito, who joined Hanna-Barbera in 1961. “Oh my gosh, that’s the old Max Fleischer studio animator!” Adds Sito (who worked at the studio in the 1970s): “Bill and Joe were very loyal to their employees and took care of a lot of people in the industry who were nearing the last quarter of their career.”

BUT THE STUDIO DOORS were always open to newcomers as well. Iraj Paran, for instance, was still in art college when he showed up at the Hanna-Barbera building looking for a summer job. “A kind, white-haired man named Bill Hanna looked at my portfolio and then said to go see the production manager,” Paran recalls. “I was hired in 10 minutes.” In time, Paran became head of the show title department. With so much production going on, Hanna-Barbera eventually had to outsource work to studios in Australia and Asia, not only bringing international artists into the industry, but establishing what would become the TV animation norm.

From the 1960s on, several other animation studios arose to run Hanna-Barbera competition, but none succeeded in knocking them off their throne. “Now that the networks had a studio like Hanna-Barbera, which was turning out shows on budget and on schedules, they would say, ‘You know, that’s a true-and-tested studio, so let’s go with them,” Ito says. Only in the 1990s, when a host of new networks altered the TV animation marketplace, did Hanna-Barbera slow down.

Six decades after Bill Hanna and Joe Barbera changed the television landscape, people are still responding to their creations. Artists and writers like Ito, Eisenberg, Paran and story man Tony Benedict, who were there in the studio’s formative years, remain in demand for interviews and convention appearances.

“The first few public appearances, I didn’t get up to speak,” says Benedict, a key writer from the early 1960s, “but after a while I got it, and the responses from the audience filled me in with a lot of information I didn’t have about myself, and how we made these pictures!”

Willie Ito perhaps puts it best: “If there was no Hanna-Barbera, and the TV industry never took off like it did, I don’t know where the so-called Golden Age of Animation would be.”

MICHAEL MALLORY is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist whose books include Hanna-Barbera Cartoons.

MICHAEL MALLORY is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist whose books include Hanna-Barbera Cartoons.

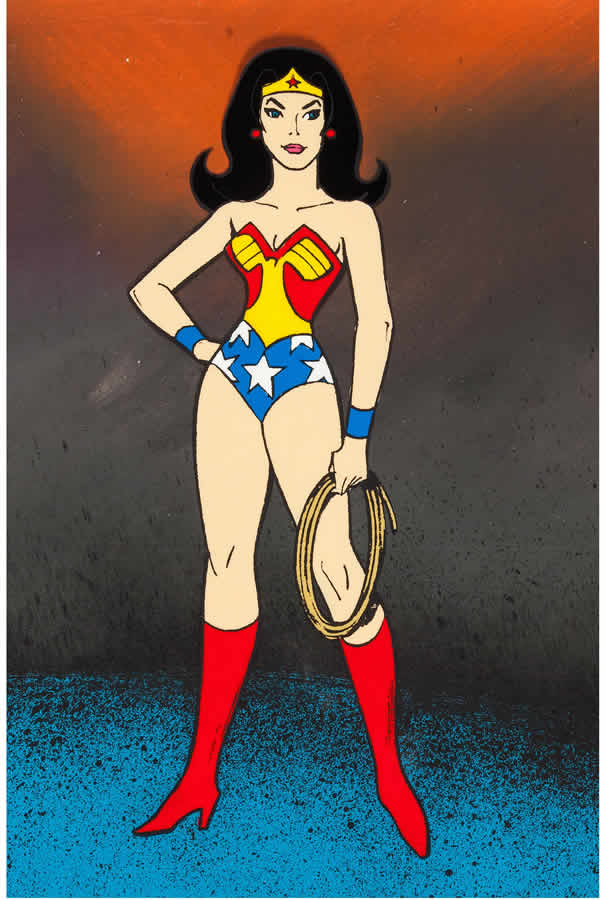

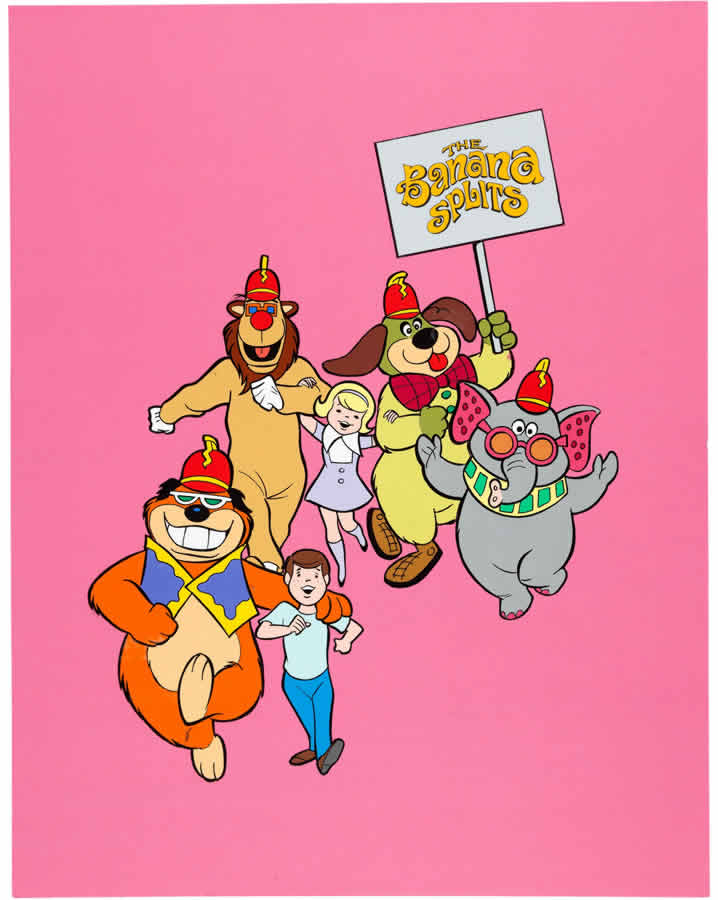

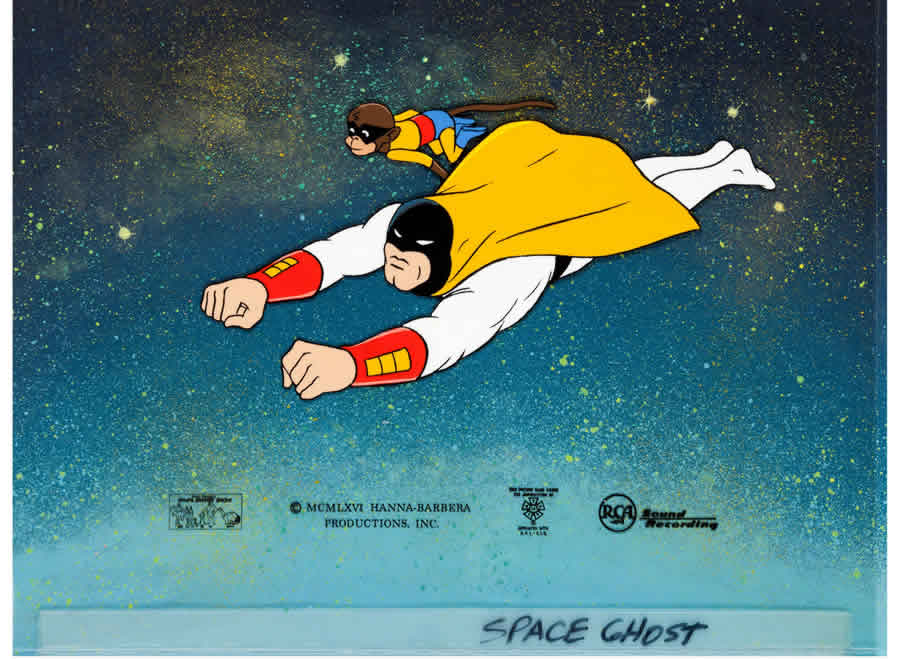

Hanna-Barbera’s Unforgettable Characters

Completely Rad

NEW BOOK DIVES INTO 1980s ANIMATION

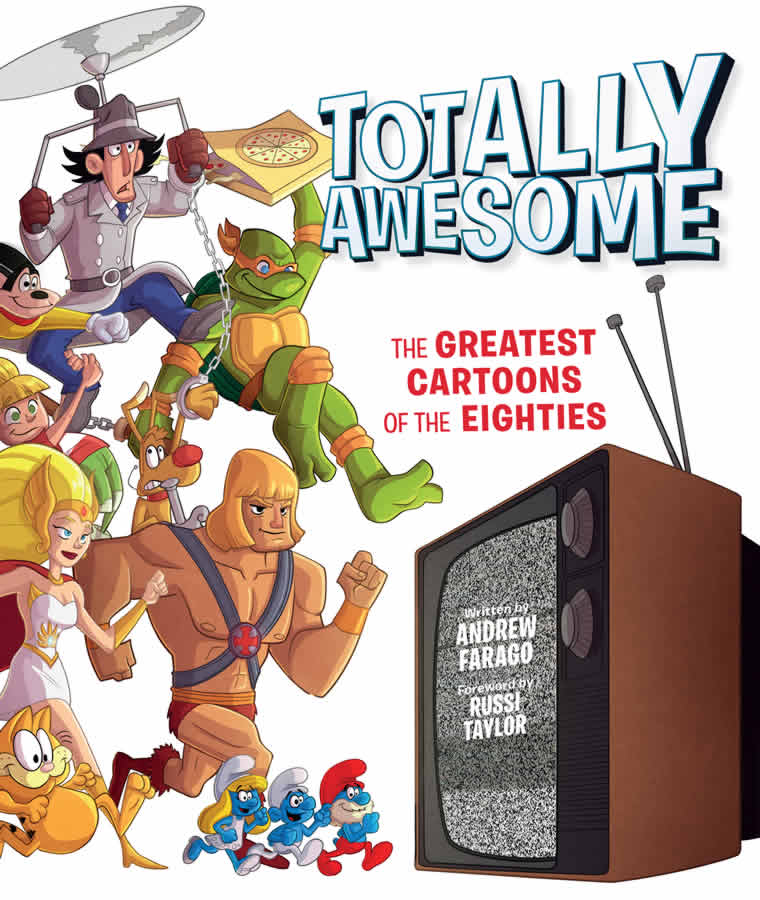

The fascination with the ’80s continues with cartoon historian Andrew Farago’s new book, Totally Awesome: The Greatest Cartoons of the Eighties ($34, Insight Editions). The book bills itself as the “ultimate guide” to eighties cartoon nostalgia, featuring the art, toys and stories behind icons like He-Man, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, G.I. Joe, and Thundercats.

Farago

Photo by Amy Osborne

Farago is curator of San Francisco’s Cartoon Art Museum and author of the Harvey Award-winning Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Ultimate Visual History, and the upcoming Complete Peanuts Character Encyclopedia.

What sets the ’80s apart from other eras in cartooning?

One of the biggest changes in animation during the eighties was the deregulation of commercial content, and we saw a huge influx of cartoons sponsored by toy companies. Syndication took off at the same time, and local affiliates were required to air a certain amount of programming for children each week. That led to an unprecedented increase in the creation of kids’ content.

A cynical take is that you suddenly had a lot of half-hour toy commercials on TV, but the creative talents behind the shows had fun with them, and kids embraced them. Even the most toy-driven shows had heart and had characters that the audience loved.

Is there one show that epitomizes the decade?

The Smurfs ran from 1981-90, and managed to encompass family, community and good moral values while also moving an incredible amount of merchandise ranging from record albums and T-shirts to breakfast cereals and plastic figurines.

At the tail end of the decade, though, you had the incredible New Adventures of Mighty Mouse that managed to confuse audiences, anger network executives, and was about as far removed from commercial considerations as a major network program could be. The eighties really did have something for everyone.

Who would you say are the most important creators to come out of that era?

It’s been fun learning about all the overlap between my favorite shows in the eighties. Russi Taylor, who wrote the intro to Totally Awesome, voiced Baby Gonzo on Muppet Babies and Huey, Dewey, and Louie on DuckTales, and she’s still going strong as the voice of Martin Prince (and others) on The Simpsons.

Creative talents like Paul Dini, Bruce Timm, and John Kricfalusi paid their dues and worked their way up the ranks in the eighties, then became some of the biggest names in animation in the nineties. And so on. It’s all connected.